Image: Promega Corp.

Image: Promega Corp. When astronauts explore space, they are exposed to extremely high levels of radiation that puts them at risk for many health conditions, including cancer, bone loss, central nervous system damage, and more. As a result, 20 years ago, NASA funded research to find a new, more effective way to measure the impact of radiation on humans. Now, this research is being used in a newly developed cancer treatment here on Earth.

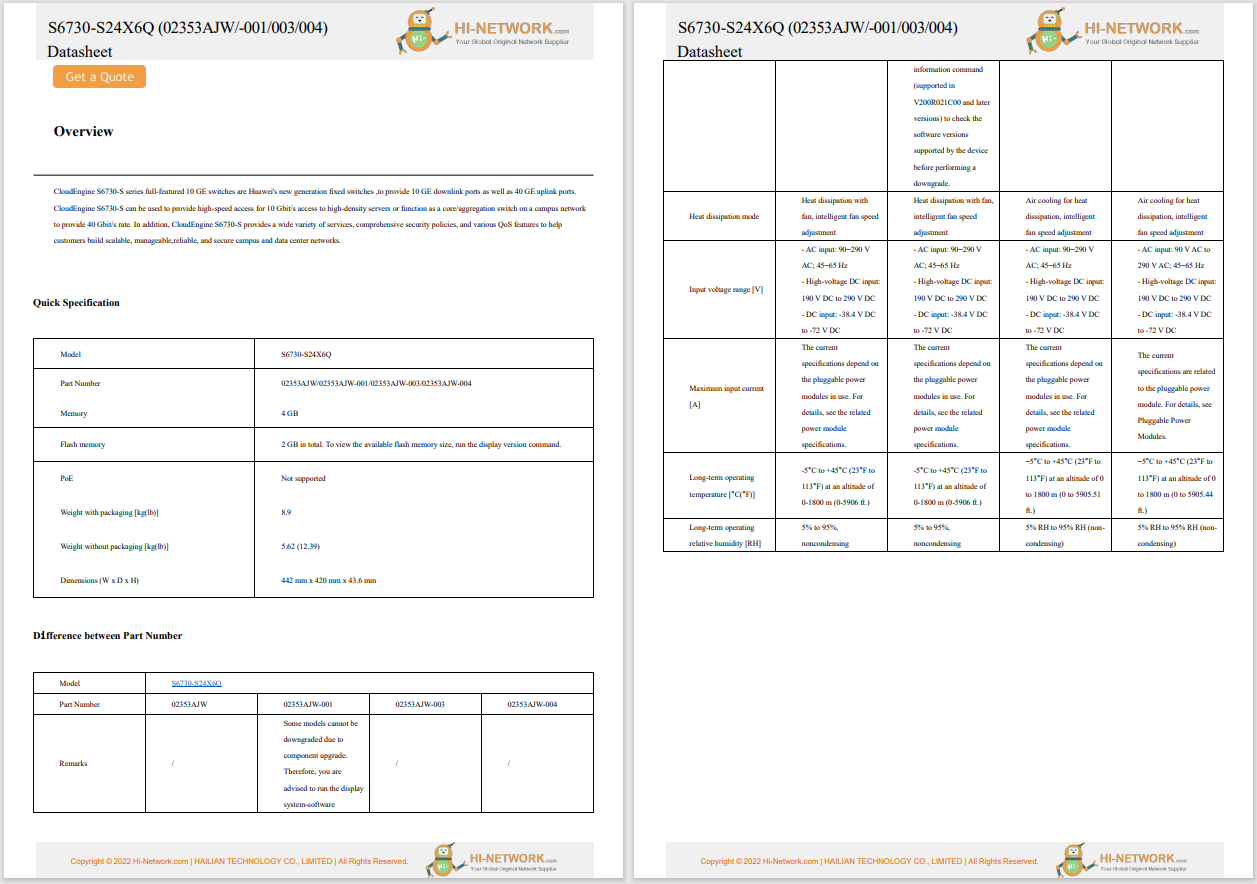

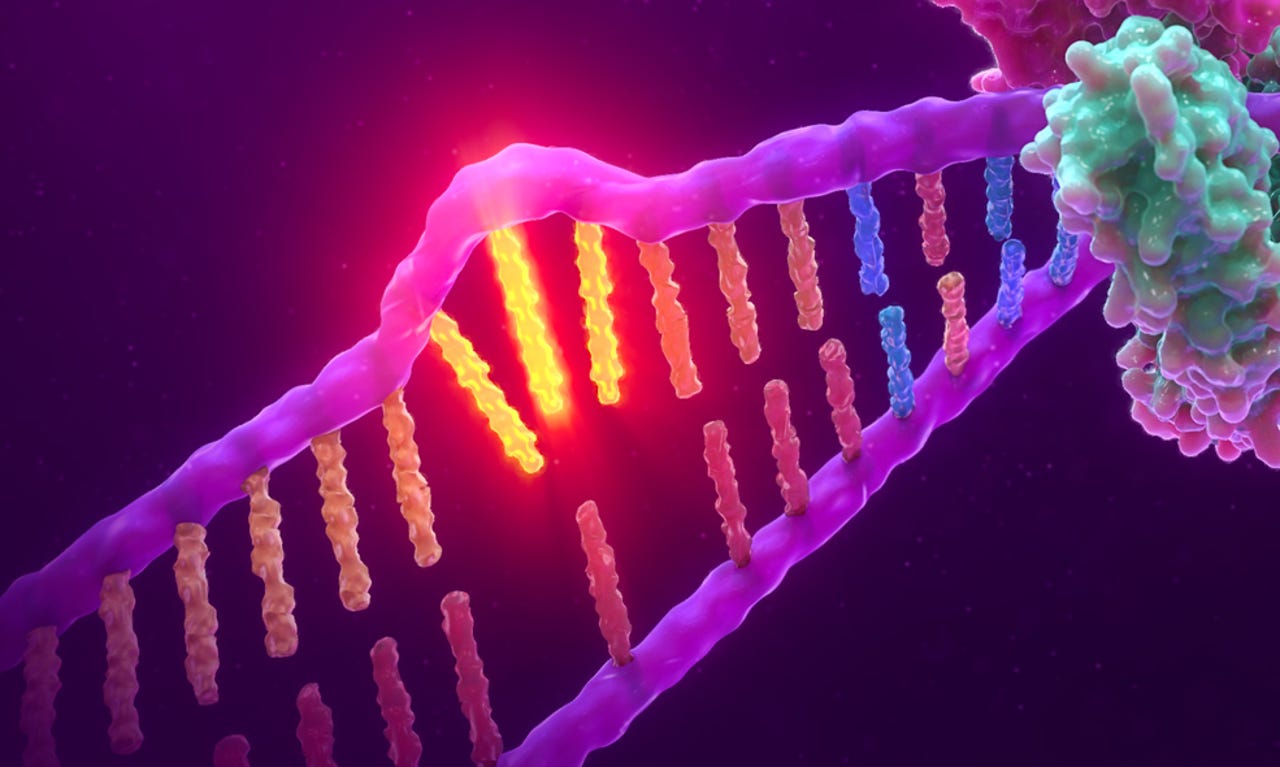

In 2002, NASA's Office of Biological and Physical Research funded research that studied whether specific pieces of DNA, known as microsatellites, could record radiation damage over time.

The findings showed that some microsatellites are more susceptible to radiation damage. They accumulate radiation damage and can, therefore, be used as an accurate indicator of an individual's exposure levels over time, according to NASA.

"The goal was to develop a method to measure a personalized radiation exposure using microsatellites as the indicator, or marker," said Jeff Bacher, the senior scientist with Promega Corporation who led the study. "Was there a one-to-one relationship between the radiation exposure our samples received and the detectable damage?"

Also: NASA kicks off UFO study with 16-member team

Although using microsatellites as a biomarker in testing wasn't a new concept, the study showed that these microsatellites could be used to screen for cancer tumors.

In a search for even more sensitive indicators, the team discovered that a type of microsatellites, certain groups of long mononucleotide repeats (LMRs), would be an ideal indicator as the mutation frequencies in these parts of DNA went up as the exposure to radiation did.

It was this discovery that led to the development of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved test OncoMate.

OncoMate is used as a preliminary test for Lynch syndrome screening and diagnosis. Lynch syndrome is a gene mutation that affects 1 in 279 people and increases risk for certain types of cancers including colon, stomach and ovarian. OncoMate makes it possible to monitor for and find some of the most treatable forms of cancer, according to NASA.

"With that improved detection, we can better help physicians and patients make good decisions about treatment options. That's where the broadest impact is," said Annette Burkhouse, medical affairs officer for Promega.

To find more beneficial uses for the test, Promega is supporting an additional nine research studies across the globe.

Hot Tags :

Health

Genomics

Hot Tags :

Health

Genomics